Ahead of its NoBudge premiere, the writers-directors talk about their college-set debut film, its influences, and how to make art when it feels like everything’s been done

Adrian Anderson and Patrick Gray would be quick to tell you they aren’t philosophers. But their myriad artistic influences — early De Palma, Comedy Bang! Bang!, Donald Barthelme, Bob Dylan to name just a few — and eagerness to pay homage to them represent a kind of philosophy, one that favors playfulness over precision, community over individualism.

Their debut feature, Pomp & Circumstance (2023), is a college-set ensemble comedy with heady doses of social philosophy, architectural theory, literature, sketch comedy, and karaoke. The film is steeped in these influences and bursts with a lively, can-do energy that’s tempered by an ironically self-serious, undergraduate ennui. The plot is as simple or as complicated as you want to make it, but in essence it follows three friends on their own existential journeys as they careen towards graduation. While they figure out how to move and be in life, an adjunct professor at their school runs for mayor on a ticket of egomania and Cartesianism, resulting in a farcical confluence of screwball comedy and conspiratorial thrills.

It’s rare to watch something these days that feels totally original, and Pomp & Circumstance gets about as close to original as you could hope for. Anderson and Gray are the first to give credit to their inspirations, as they do in our conversation, but finding those threads within their film is a pleasure in and of itself. What feels most special, however, is their open-hearted grappling with fundamental questions about how we define ourselves, how to make art that feels new, and our innate desires to over-interpret. The writers-directors of Pomp & Circumstance discuss their film ahead of a roadshow theatrical tour and its upcoming online release through NoBudge.

Chris Cassingham: Let’s start from the beginning. How did you guys come together as friends and as filmmakers?

Adrian Anderson: Patrick and I both transferred into Emerson College after two years at other small schools, which kind of put us in this bizarre position of not knowing a lot of people. But when we connected we found that we had a lot of very similar interests in writing, and especially in comedy. And we both introduced each other to a lot of things, so it felt very natural. We had a group of friends around then that spawned a couple of projects. And Pomp & Circumstance was the most realized one.

What kind of things did you bond over creatively or artistically?

Patrick Gray: Initially, I think Comedy Bang! Bang!: The Podcast . And ’90s sketch shows.

Anderson: Mr. Show, that kind of thing.

Gray: And then some other stuff like Donald Barthelme short stories.

Anderson: Whit Stillman, Hal Hartley.

Gray: Some of it’s pretty evident in the film.

Anderson: For a while, I saw this film as a combination of both me and Patrick’s disparate influences and interests. But now going back, I just see it as the kind of thing that we would both gush about when we were around 20. So I’m glad we’re able to make something like that.

I hadn’t really thought of the influence of sketch comedy when watching it because I don’t have a lot of knowledge of that world, but hearing it from you explicitly makes those influences shine through.

Anderson: We definitely talked a lot about finding a tone that was very slapstick. While editing, something we often talked about was the ‘Looney Tunes cut,’ in regards to trying to just make it as silly as possible. And I guess a lot of that was to balance some of the more heady, cerebral aspects of these characters’ pompous ramblings. Another big thing we talked about a lot was those Michael Ian Black and David Wain “Stella” shorts. It’s very important that that influence is on the record. (laughs)

Before we get too much into the film, can you describe it for people who haven’t seen it yet?

Gray: I’d say the film is an academic comedy that takes place in Burlington, Vermont, about three students lost in their own heads, about to graduate. One of them is looking for love, one of them is looking for meaning in art, and one of them is an artist herself — she’s a documentarian. And they all get wrapped around this ridiculous plot involving their professor who decides to run for mayor on a ticket of bizarre art theory-meets-architectural theory….

Anderson: Meets vain-glory…

Gray: And chaos ensues.

There’s so much in these 65 minutes, but the plot is kind of low on the list of things I was thinking about. It balances being narratively spare with having real thematic density. I’m curious how you arrived or decided on that kind of balance.

Anderson: It came about very naturally, both through how it started and its influences. Correct me if I’m wrong, Patrick, but I’d say the most primordial version of this was: I was writing something different, you were writing this play, which was very, very different. But it still had this through line of three college students, sort of wannabe Bohemians, that get involved with an Elvis impersonator. And then I remember you came back from work one day with this whole thing about architectural theory. This was a really interesting thread. It started to come together then.

We were thinking a lot about early Brian De Palma comedies, like Greetings (1968) or Hi, Mom! (1970) where you follow these characters, but it’s very loose and New Wavey and sketch-like, where there still is a through line, and a sparse kind of economy of filmmaking, but you get to go with these tangents. And I love tangents. I think tangents are really fun. The literature that Patrick and I bonded over also kind of flourishes in these tangents.

A lot of the film, the ideas the film explores, came from us being stuck during lockdown. We lived in different states, crashing at our folks’ houses, and we would just call each other for four or five hours and talk about art, the idea of scenes, and writing of the past. And a question that continued to emerge, especially for me — and I put a lot of this into the character of Marie — was: How do you make art in a world where, not only does it feel like everything has already been done, but you have instant access to all that information at once? How can you make interesting, challenging art that’s not just referential? And the film asks a lot of questions, but that’s kind of the essential one.

Gray: On the note of how the idea evolved, I think it’s definitely from those long conversations. I was living in Allston at the time, during COVID. I was about to graduate college, feeling Dustin Hoffman-ish, I suppose, and kind of realizing the silliness of how serious our conversations were, and then how silly that all is while I’m sparing $10 to go buy ramen.

Anderson: We were prioritizing buying used books more than anything else.

Gray: Yeah, used books and cigarettes. It was a time of just being able to watch yourself and realize that it’s pretty ridiculous, but at the same time you’re taking yourself so seriously because you’re trying to contextualize yourself in the history of Rimbaud, and Baudelaire, and Henry Miller, and Dylan, and stuff like that. So it’s like that kind of friction of, ‘how seriously should I take myself,’ against this other realization of, ‘it’s so stupid how seriously I’ve taken myself.’

Anderson: When I was talking earlier about me and Patrick bonding over these ’60s and ’90s films and wanting to make something kind of like Slacker or Kicking and Screaming, movies about being kind of stupid in your 20s, I was thinking about how those movies would age as I grew more distant from the age they’re depicting. I always think about Roger Ebert’s review of La Dolce Vita, where he talks about growing up with the film. And so much of that came from me [telling people], ‘Slacker is the greatest movie ever, you gotta watch it.’ And they say, ‘oh, that’s insufferable, it’s just a bunch of horrific college students.’ So we were like, let’s give them some real insufferable college students… ourselves, in a way.

Was there a point when you realized that there was an inherent silliness to your characters, while still being able to take them seriously?

Gray: I come from a background of writing comedy more than anything else. I did sketch and stand-up all throughout college, rather than creative non-fiction or something like that. So that cartoonish satire was the tone in which I was approaching anything I was writing.

Did that background inform your attitudes towards this stuffy, New England milieu that we see in the film? My guess is that it’s a heightened version of what Emerson College was while you were there, this sense of age and prestige that you sort of can’t help but poke holes in.

Gray: Yeah, while also feeling a kind of affection for it. I grew up working at a country club as a caddy. I was around all that and I realized how kind of flaccid it all is. But there’s also all this affection.

Anderson: I think a lot of it came from what you almost expect the ennui of the college experience to be versus what it actually was. So much of it is this affection for something that maybe didn’t exist or we didn’t necessarily experience — Emerson does not look like that; Emerson doesn’t really function like that. It’s more so this mythical, old Ivy Hall college of your imagination and the glamorization or fetishization of the brooding, suffering undergraduate academic, and how ridiculous it was.

I’m really curious how you met your actors and what their contributions were to their characters because they’re extremely specific.

Gray: Noah Brockman brought a lot of physicality to the role of Thomas. He reads passages from The Sorrows of Young Werther in it, and he embodies that kind of world weary character. Or, he’s wanting to be world weary, and wanting to play the role of this romantic, and then in playing that role desperately wanting to cast the people around him as characters in this romantic tragedy.

Anderson: I met Noah three days before lockdown went into effect in Boston at Harvard Film Archive’s Kelly Reichardt retrospective before First Cow came out. We met at a double feature of River of Grass and Night Moves. And we both went to Dunkin Donuts and ordered small black coffees. We spent all day hanging out and I thought he was kind of an interesting guy. I wrote the Thomas character kind of based on him with Patrick, even though Patrick had never met him. We’ve since all become very close friends.

A lot of the film was very spare on the page. A lot of the leads we ended up working with were comedians or stand-ups or people from the world of sketch comedy, and that lightened it a lot. Ben Loftus, who plays Charlie, I knew him from stand up. And his stand-up persona definitely formed a lot of the character in the performance of this little wide-eyed liberal, sort of bleeding heart, but maybe not always with the greatest intention.

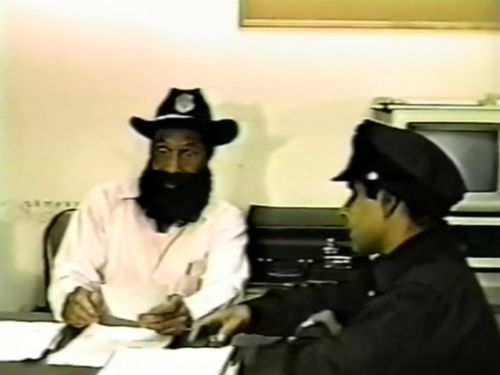

Tell me about Patrick Malone, who plays Professor Cherry.

Anderson: I’ve known Pat for many, many years. We got our start playing music together when we were teenagers in the Worcester, Massachusetts, folk-punk scene. He was a little older than me, and I really admired him. He did a little bit of community theater, but he never really acted before, and I just couldn’t think of anyone else for this role. He obviously brings this manic energy to it that is so important for the film, but it’s also these moments of levity, too. We ostensibly, until the end of the film, only see him in a classroom, as you would a professor. And it was important that those scenes are through the eyes of these students, as opposed to merely fleshing him out a bit more — because that’s how he wants to be perceived.

What about Isabel Zaia, who plays Marie?

Anderson: Izzy is another close childhood friend of mine. She’s kind of an insert character in many ways. But a lot of her performance comes through voiceovers and through the films she creates, which are these loving, hyper-specific parodies of different forms of experimental films. The biggest thing I remember of working with Izzy and what she brought to the performance, is really getting her to go for it in the voiceovers, because you don’t necessarily see her, you see her work. At the end of the movie each of the three leads come to their own conclusion on how to move forward, and I think Izzy is maybe the most hopeful.

I don’t want to get too mired in the specifics of all the theoretical and philosophical stuff the film is packed with, but I’m curious about your approaches to making not necessarily the philosophy itself funny, but the scenarios and context you put it in funny. This film reads as having been made by people who have a deep understanding of all of it, which might give you the freedom or the confidence to make fun of it. Is that the case?

Gray: A lot of the time we approached it as if we don’t actually have that great understanding of it. All of it is just my idea of, for example, Frederick Jameson.

Anderson: I came to that conclusion, personally. These characters, like us at times, don’t really know what they’re talking about. They’re kind of just regurgitating. Ultimately, it’s people speaking in quotes to one another and they kind of struggle to speak as themselves.

Gray: I don’t want to be too self-deprecating and say the film doesn’t know what it’s talking about, but it’s always qualifying whatever it’s talking about by holding back any commitment to anything it or the characters are saying. That thing of, you know, I can justify what I say by saying that it’s a quote from somebody else.

Anderson: It not only goes to having a legitimacy, but also, almost feeling like you’re in a lineage of some kind. But it is a film about young people trying to find their place, and I don’t think it’s trying to cast judgment on it at all. It’s a part of a necessary philosophical and mental growth.

I really came away from rewatching the film with this understanding that we can’t really ever temper our desire to interpret things. It’s one of the most fundamentally human instincts to try and make sense of stuff. So it’s folly to try and arrest that.

Gray: Maybe my coyness about understanding is just the film, I think, presents a great fear of seeming pompous or seeming like you’re trying to rise above some type of regular guy, intellectual thing.

Anderson: There is that desire of wanting to be the smartest person in the room, but there’s also the fear within that of being too eager to be perceived in that way.

It’s like a feedback loop. You’re in this very specific, academic place, so you don’t want to seem like the dumbest person there. But there’s also this rejection of seeming too much.

Anderson: Ultimately it’s a bubble. At the end of the day a crowd of 14 people in a college town watch this guy’s speech as he implodes. There is no straight man. You’re stuck with these people because I think we’ve all been them whether we like to admit it or not.

When you first started conceiving of this film, did you have any sort of grand notions about what this film would be and maybe mean, and were they met or subverted by the end of the whole thing?

Gray: When I initially started writing I was trying to find some sort of thematic reconciliation between how you see yourself and how you’re seen by other people, and a lot of that was put into Noah’s character. Thomas sees himself in one way, and he’s so anxious to make sure that everybody else sees him that way. Or with Elvis, he sees himself that way, so he dresses up that way to make sure other people see him that way. Or James Cherry sees himself in the image of le Corbusier. Or Marie, who sees herself as someone like Maya Deren, so she dresses her films up to make them look like that. And with Ben’s character, it’s the same thing. He wants to try to manipulate how other people see him so he can justify how he sees himself. I think that the film ultimately does stay true to that theme. A lot of things evolved, but that core anxiety I felt within myself definitely carried through the whole way.

Anderson: I think a big evolution was how certain tonal things [developed], especially through the edits. The script was a little colder on the page and the film is maybe a little more warm-hearted. A lot of that came through finding the comedic beats in the edit — and also finding that ending, too. I would be remiss if we didn’t talk about a big bonding point between me and Patrick, which is Wes Anderson. I’m desperately trying to not use words like ‘feel-good’ or ‘sentimental,’ but just ending on that moment of making something again with Izzy’s character, Marie, that was something that just wasn’t in the script, which originally ended on a more cynical, darker note.

In broad strokes, could you walk me through the production process — where you were, how long things took?

Anderson: It took a while. One of the big logistical things when you’re making a movie of this size, especially being a location shoot, is trying to keep things as concentrated as possible while filming around people’s schedules. We shot in Vermont and Boston because of that. We found parts of Boston that could pass as Vermont. Certain people were still in school, some people had work obligations, so you have to work around that. And on top of that, you’re living in an Airbnb with like 12 other people and some of these people have never met before, and you have to manage all of that. The majority of production happened in mid-2021.

Still dark times.

Anderson: COVID was loosening, but widespread vaccination hadn’t really happened yet. So we were trying to keep it as tight a bubble as possible, which is always difficult, because if people are in a new place they want to go out and explore. So getting everyone locked in out of necessity was somewhat of a challenge.

Gray: Yeah, that was the main thing, containing everything. Living for about a week or so on the floor of a basement. It was freezing because it was March in Vermont.

Anderson: There are a lot of locations, a lot of people, and we had a very limited budget and a very limited amount of time, so we often had a B unit working at the same time as everything. One of our associate producers, Ian Butterfield, actually taught Izzy how to use the Bolex, so all that footage at the end is stuff she captured herself for the film. And, for example, say we’re setting up a big Elvis dolly shot, someone in another unit is outside preparing the scene with Noah and Davey Tanner (A.K.A. Bunny Boy), the folk musician. I remember operating with the mindset that there’s always something we can be capturing. It definitely was something that was aided by us being co-directors as well.

We did reshoots in Connecticut in March 2023 with Pat. We reshot a lot of the lecture scenes. It felt very easy and interesting to go back to refine exactly what we wanted to say. That’s something that is aided by the structure and modular format of the film. It may have been more difficult if it was a more conventional, narrative picture.

Pomp & Circumstance won the Audience Award at the Tallahassee Film Festival last year. What was that experience like?

Anderson: Neither of us had done the festival circuit before. And I was on set for a different film when I got the news. Steve Dollar and Chris Faupel of Tallahassee were just really, really, really receptive, and made us feel like they had something special on their hands. I remember we ended up sitting on the side of the theater, just watching everyone’s reaction, because, it being a comedy, you want to see what works and what doesn’t. I don’t think we’d even seen it in that large of a group yet. You spend so much time with a movie alone, so that was great.

Gray: I have so much anxiety about being on exhibit, but people seemed enthusiastic for our enthusiasm and the film’s enthusiasm for it being a film. We have both kind of drowned ourselves in film history, so a lot of it came from the film’s wide-eyed enthusiasm for film itself. Watching it, I think you can tell we had fun making the film. It was made by a group of friends and I think that comes across.

Anderson: It was also really rewarding to see the film embraced by audiences as a comedy. People may be a little put off by some of the more philosophical things the film immediately throws at them, but to see it kind of just work and be embraced by audiences as a comedy was really, really rewarding.

Are there any specific responses to the film that have stayed with you?

Anderson: When we played in Kansas City, we had a lot of people come out, but not a lot of them stayed to chat, which was fascinating to me, because it’s a small film at a small film festival. Then I saw them review it on Letterboxd and they would give it positive scores, which is great, but why didn’t you come say hi? It’s funny, because in our festival run the first three or four were very concentrated, all outside of New England, and I thought there would be some sort of culture shift, or something would be lost, or maybe this Northeastern academia thing was being read as almost exotic, to a degree. But the reception has been enthusiastic, and we’ve won a couple other awards since then. It’s just kind of incredible because we’ve never done this before.

And one of the wonderful things is we were able to make a lot of friends throughout the circuit. We played back-to-back with Ryan Martin Brown’s Free Time. And there’s Jack Dunphy and Jordan Tetewsky. Jack and I were on the set for his latest short when we both found out we were going to Tallahassee. He continues to be invaluable as a resource for navigating this world. It’s difficult as a young filmmaker. If you want to be a welder, you can go up to someone who’s been welding for a while, but it’s a little more difficult in terms of independent, micro-budget filmmaking. So being embraced by a part of a community has been really, really wonderful.

Another community you’ve been embraced by is NoBudge. They’re giving the film online distribution in July. How did Kentucker Audley come across the film?

Anderson: We just submitted it the normal way through NoBudge’s FilmFreeway. I had seen Kentucker’s films before, and I’m a big fan of them. And it’s especially cool how he has created this lineage through his involvement in early mumblecore films in the early 2000s, his short-form stuff, and his Factory25/New York works. One of the coolest things about NoBudge to me is its regional section, where you can see all these films from the Southwest, all these films from California, all these films from the Pacific Northwest. We have friends, people that were in this film, that are featured in the New England section, too. It’s really accessible and has built a real community, and I’m really proud to be there.

Pomp & Circumstance will be available soon on NoBudge

If you enjoyed reading this interview, please consider subscribing or contributing to Split Tooth’s Ko-fi! (We promise we aren’t buying coffee. All proceeds go to our writers and to maintaining the site.)

(Split Tooth may earn a commission from purchases made through affiliate links on our site.)